In a remarkable showcase of community power, Ford City Park is experiencing a transformation, championed…

A Town of Immigrant Farm Workers Says No to an ICE Detention Center

By Miriam Jordan—Feb. 20, 2020

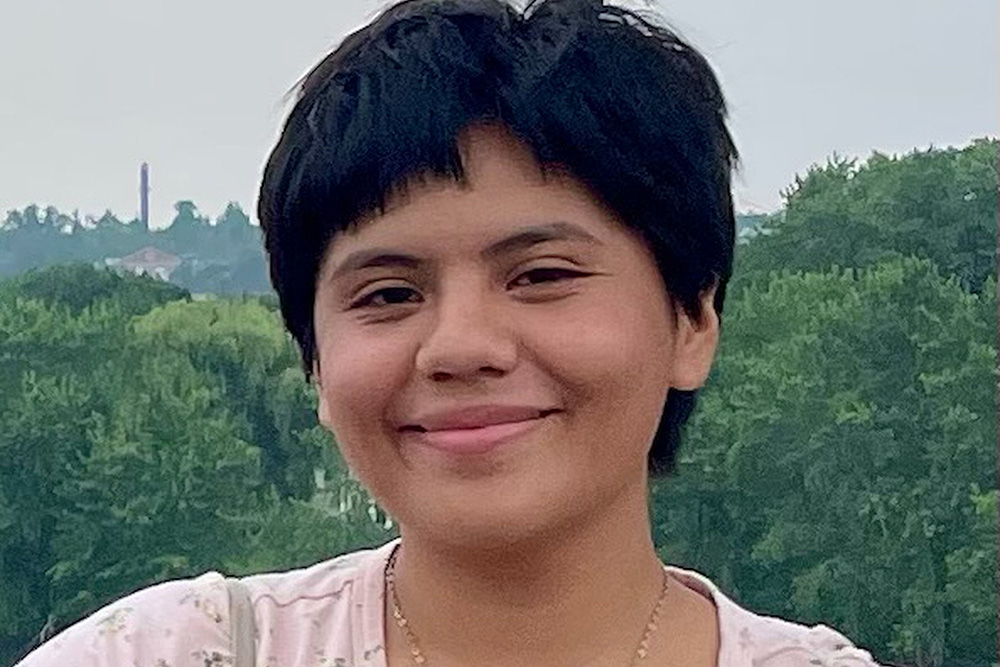

As an undocumented immigrant, Maribel Ramirez does not officially have a say in the affairs of the small agricultural town in California’s Central Valley that she has called home for 20 years.

But late into the night on Tuesday, she stood with hundreds of field workers and other residents outside McFarland’s City Council chambers, a bullhorn in her hand. “No ICE! No GEO! We’re farmworkers, not delinquents,” they chanted in Spanish, led by Ms. Ramirez, 42.

At issue was a multi-billion-dollar corporation’s proposal to convert two state prisons slated for closure into detention centers for undocumented immigrants, operated under contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement — a plan that city leaders said could provide this impoverished town with a financial lifeline.

A new law in California outlawing private prisons will cost the city $1.5 million a year in taxes and other fees paid by the prison corporation, the GEO Group, unless the company can convert the two facilities it has operated there into immigration detention centers.

McFarland, which gained its only previous measure of fame in the 2015 Kevin Costner movie, “McFarland, USA,” lis home to thousands of workers like Ms. Ramirez, who toil in the vineyards and the almond, pistachio and citrus orchards that stretch out in every direction. Up to half of the city’s 15,000 residents, according to private estimates, are undocumented — the very kind of people who might be housed behind bars in the facilities that until now have been sheltering criminals.

“Without GEO, we can’t guarantee we can pay for law enforcement, fire or any other services,” Mayor Manuel Cantu cautioned on Wednesday, a day after the city’s planning commission, bowing to overwhelming public sentiment, voted against the proposal.

Mr. Cantu, who announced his resignation as mayor on Wednesday, predicted that closure of the prison facilities, in a city already facing a $500,000 budget deficit, would be “devastating.”

But he appeared resigned: “If the residents don’t want them because of their fear of ICE or whatever, the city belongs to the residents,” he said in an interview.

The company could appeal the planning commission’s decision to the City Council, but residents made it clear they would do whatever they can to block the plan.

Tuesday night’s commission meeting saw a stream of residents come to the podium, urging city leaders to remember who lived in their town.

“You can find other options, but don’t bring ICE. In the long term, the McFarland community will suffer,” said Estevan Davalos, an undocumented farmworker from Mexico who has lived and worked in McFarland for years.

Rural, cash-strapped cities across the country have increasingly relied on private prison companies for tax revenue, jobs and other financial benefits to stay afloat.

But the private facilities have been criticized for promoting incarceration and lacking oversight. The new law in California also prohibits private immigration detention centers, but the GEO Group signed an agreement with ICE to operate the proposed facilities in McFarland before the law took effect — leaving the final decision in the hands of the planning commission.

In Adelanto, Calif., where the GEO Group already operates an immigration detention center, the city planning commission on Wednesday voted to approve a permit to convert another state prison, also run by GEO, to house immigrants.

Ms. Ramirez, who helped organize the opposition in McFarland, said she was just 22 when she crossed the border from Mexico, found work picking grapes in McFarland and started a family.

In all their years in the little town, she said, neither she nor her husband, Eusebio Gomez, who is also undocumented, had ever encountered immigration authorities.

“We have lived here in peace. We built our lives in McFarland, working to support our family without any fear,” she said.

Her son Jesus made straight A’s in school, a source of pride for Ms. Ramirez, who is illiterate. Eusebio Jr. excelled at soccer and worked in the fields during his summer vacations to help the family.

Feeling settled and secure, the couple last year began discussing with their landlord the possibility of buying the two-bedroom house that they have rented from him for 13 years.

Then one day in mid-January, while she was pruning grapevines with her new red shears, her crew leader told her about a plan to refashion the prisons downtown into ICE facilities.

“Those two prisons three minutes from my house, they never bothered me,” said Ms. Ramirez, sitting in the tidy kitchen of her house before heading downtown for the protest march and hearing on Tuesday. “An ICE detention center, that would bring fear to our community. We might have to leave.”

Both GEO and the Justice Department have sued the state over the law banning new or renewed private prison contracts. In a bid to circumvent the law, signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in October and effective in January, GEO and ICE signed an agreement in December to turn the state prisons in McFarland into federal detention facilities for immigrants, which they contend would still be legal.

That’s when the community got to work.

Faith in the Valley, a local nonprofit, gathered people at St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church and organized groups to distribute petitions. Each afternoon after finishing her shift in the vineyards at 4 p.m., Ms. Ramirez and her oldest son joined dozens of other people knocking on doors to inform the community and seek support for their campaign.

They asked people to fill out their name, address and phone number on a green commitment card that read in Spanish, “No to Immigrant Detention Centers in McFarland.” They laid out what was at stake to whomever would listen.

“Some people slammed doors on our faces,” said Stefani Davalos, Mr. Davalos’s 17-year-old daughter, who went door-to-door with her father. “Others were afraid to sign. But a lot of people, even though they didn’t have papers, agreed to fill out the card.”

Read more at The New York Times.

Comments (2)

Comments are closed.

If THOSE WORKERS HAVE BEEN IN THE UNITED STATES FOR THAT MANY YEARS, THEY SHOULD HAVE TRIED TO BECOME US CITIZENS INSTEAD OF WHINING ABOUT THE GEO, THEY NEED TO BE IN THE UNTIED STATES LEGALLY, AND THEN THEY WOULD NOT HAVE TO FEAR ICE, IF I HAD BROKEN THE LAW I WOULD HAVE TO PAY THAT PRICE, THEY ARE NO DIFFERENT, THERE IS A RIGHT WAY AND A WRONG WAY TO DO THINGS, HOW CAN I TEACH MY CHILDREN RIGHT FROM WRONG WHEN YOU HAVE ILLEGAL WORKERS HERE WHO THINKS THEY HAVE RIGHTS, NO THEY HAVE NO RIGHTS I KNOW PLENTY OF IMIGRANTS THAT HAVE COME TO THE US THE LEGAL WAY

Thank you for taking the time to share your perspective.